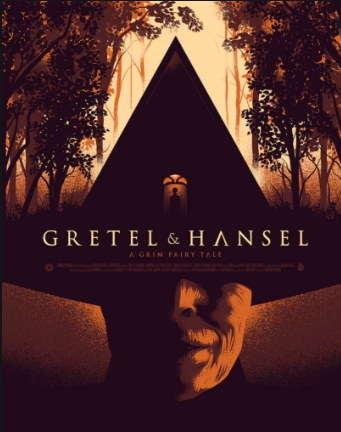

Symbolism in Gretel & Hansel: The Divine Female and the Number Three

Back in the day, the purpose of fairytales was to be scary. Before Disney came along and turned them into wholesome family fests, fairytales were warnings meant to be didactic terror tales. Gretel & Hansel is a visually stunning take on the classic fairytale chockablock with symbolism and a deep meditation on the female. Many have said that it is more style than substance, but that’s only on the surface. Dig deeper and there is plenty to analyse and pick through.

From IMDB: A long time ago in a distant fairy tale countryside, a young girl leads her little brother into a dark wood in desperate search of food and work, only to stumble upon a nexus of terrifying evil.

Much like Robert Egger’s The Witch (2015), every frame in Gretel & Hansel is perfectly shot—like an oil painting—and perfectly centred. It was shot at 1:55 aspect ratio, almost as though the cinematographer decided to follow the “block of three” photography principle and never strayed from it (another three here, which we’ll talk about more later). You don’t need to move your eye very much in order to take in the film, unless, like me, you’re looking for all of the delicious symbols peppered throughout the film.

THE NUMBER THREE

Threes are everywhere in this film, which intrigued me to the core of my being. Three is my number. I’ve written many essays in my life about the number three, my favourite being an essay on the number three in Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. Three is the number of magic, the trinity, of mysticism and gnosticism. It is the (approximate) number of pi, and, my favourite: it is the number of the three fates (the maiden Clotho, the mother Lachesis and the crone Atropos)—also relevant to this film. The film follows Gretel on her journey from girl to woman. She represents the girl, and the woman, where the witch represents the woman and the crone.

From the triangles scattered throughout the film to the three main characters, threes are everywhere. When Gretel looks into the witch’s house, she does so through a tiny triangular window that, from the other side, looks strikingly like the Eye of Providence, which is a symbol used to illustrate God watching over all of humanity. There may be something in there—a commentary on what is to come and Gretel’s rise to being all-powerful? More threes occur throughout the film—the three figures Gretel sees in the woods; the three versions of herself reflected in the mirror; each mirror pane containing the reflections of three dead children; the three corpses on the bloodied table (lots of period references here too, by the way—more on that when we discuss the feminine). I’m sure that with a careful re-watch, I could find more threes than I know what to do with.

Intriguingly, when there is danger in the film it is often accompanied by a square of a rectangle and the colour red (again, see later about femininity and the female). It is also interesting to note that the shape on the door of the house where they started, and where Hansel ends, is a circle—the first circle I remember seeing in the film (we only see it at the end, not in the beginning where they start), perhaps to symbolise the fact that Hansel has come fill circle? Perhaps to distinguish between the feminine and the masculine? Something else to ponder.

Femininity and the Female

It seems obvious that the movie is a meditation on the female. How females have been trapped. How females are always the caretaker. How females always have to sacrifice something. How females have, as the film quotes more obvious uses” than skills like herb-lore and witchcraft. How females are targets. But also how women have power. And how women wield power. How women can be the danger. Gretel’s name coming first in the title is no accident.

Throughout the film, the colours pink and red (blood and girlhood) are used to indicate danger. The girl in the pink hat; the pink smoke turning red; the pink bindings holding Gretel down. Again, this symbolism is intriguing. A reference for growing from girlhood to womanhood? Red is the colour of danger—and is used to that effect in the film as well. Ah, women and our periods. Women and the blood we spill giving birth. Women and blood, blood and women. It is the stuff of life—and of death.

The movie is both a meditation on the power of women, the danger of men and a commentary on the sacrifices women have to make for power (or the perceived sacrifices). With a disgusting old man and potential employer enquiring after Gretel’s maidenhood to the vivid red of her period, from the abandonment of the children’s mother to the final reveal of the witch devouring her own children—the film is a commentary on what being a woman is. Percolated with the colours red and pink, where both are used to illustrate danger, it seems obvious that this is a film about the raw power and fear of womanhood. Even the hallucinogenic mushrooms the children consume are vividly red and eventually lead them to the witch in the woods. In the end, both Gretel and the Witch, Holda, have to make sacrifices (eat your children, be the caretaker for your brother). Gretel sends Hansel away “with a part of herself freely given”, turning sacrifice into a gift.

Three little windows above her head.

Nature is also a heavy theme here, relating to both witchcraft and women (women, like all of nature, go through cycles, as does spellwork and witchcraft). There is a time to plant and a time to harvest, there is a waxing and a waning moon, there is a time for fertility and a time to be barren. Gretel ends up bending nature to her will as she comes into our powers, which might be a powerful (and brilliant) meditation and symbol of women (and Gretel) taking their own power into their own hands.

The film is a giant female coming-of-age emancipation.

While I enjoyed this film immensely and will be buying it for my collection when he DVD is released, I found the ending too heavy-handed. Gretel’s voice-over could have been omitted for much greater effect. It took away from the film’s mesmerising cleverness; as though the director didn’t trust the audience to be clever enough to understand it without the heavy-handed monologue attached. I should also note that I did not understand the the strange zombie creature that the monk/priest kills while attacking Hansel… it seemed out of place and random.

Gretel and Hansel reminded me, in a strange way, of the novel The House in the Dark of the Woods by Laird Hunt (which is brilliant and you should all read).

Have you watched Gretel & Hansel yet? What did you think?